One of the greatest things about being in medicine is that we are lifelong learners and lifelong teachers by trade. Good physicians teach their patients about health (hopefully), their bodies, and proper management of their diseases. In addition, those who chose to stay in or stay involved in an academic setting get the opportunity to teach the next generation of physicians. As a student, the resident physicians and attendings that taught well were very much appreciated, and it is nice to be able to do the same for current students.

I used to think that great teachers were great regardless of who they taught. I still think that's true - but only to a certain degree. As a student, you are exposed to different types of teaching styles, but you are the only measuring stick for what a student should bring to the table. As a teacher, you are exposed to different types of students, and I have to say, students and their eagerness (or lack thereof) to learn taints the teacher-student relationship. Those who are in the field of education may chuckle at this obvious observation, but for those of us not officially trained to teach, this was a delayed but eye-opening realization.

In medicine, there is a lot of informal and formal teaching in the hospital. Students rotate on different medical specialties each month, and while many do not know what specialty they would like to pursue, some seem to have been born knowing that they were meant to be a pediatric interventional cardiologist (or some other ultraspecialized field). Still, even for those who have their hearts set on a particular field, most are still very open to learning all they can while on the different specialties. After all, if you're going to be a pediatric interventional cardiologist, your only exposure to internal medicine will be the few months you get during your medical school training. In addition, you will be a physician as well as a ultra-specialist - more reason to try to learn general aspects of medicine - and really, friends and family are going to ask you questions about general medicine, regardless of how specialized you become. This seems like common sense, but we've had a series of students come through that apparently don't believe that it's important to pay attention when rotating on their basic internal medicine rotation. A little scary...

It's been a challenge to try to figure out how to best teach this small group of students. Some of them are not interested in any teaching and just try to do the minimum to get by. Unfortunately, as everyone is busy on the wards, if you do not want to be taught, I probably will teach you less and less as time passes. Other students don't want to do any reading or learning on their own, and just want you to spoon feed them everything. There is no such thing as a dumb question, but there certainly are questions that show that you really didn't pay attention in medical school classes and you didn't bother to try to read the basic information every student should know. Medicine is a lifetime of learning! You need to not only learn as much as you can while training, mainly from reading about diseases that you come across, but you also need to learn how to teach yourself (where to find answers to questions) for the rest of your life. If you don't do this, what will you do after you are done with residency and go out into the real world? Will you stop learning because no one is there for you to ask questions to??

I had a couple of students like this in a row, and it was a little unsettling - as it was the first time I had seen this, I was trying to make sure that it wasn't the teacher or the teaching style that was creating this situation. Luckily, along came a student who wanted to learn, and that month was spent happily teaching her basics and clinical pearls of internal medicine. I'm still not sure that students who seem like they don't want to learn mean to be that way. Maybe it's a difference in culture at different academic institutions, or maybe it's something else... all I know is that when the student doesn't want to learn, the teacher does not want to teach.

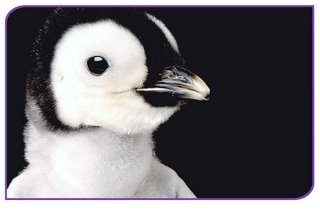

March of the Penguins - If you don't know what this is, you're missing out.

March of the Penguins - If you don't know what this is, you're missing out.